How can Brian Eno, Maurice Sendak, Christina Lamb, William Goldman and Henry Watson Fowler can improve your copywriting?

There are many guides for copywriters. Some are really very good. Some.

Copywriting is one discipline that relies heavily on creativity, and this means constantly exploring new ideas. Many of these ideas will come from somewhere other then copywriting. Let's face it, if you only read copywriting manuals, it would make you an expert on... copywriting manuals.

One way to improve your copywriting is to pinch ideas from elsewhere. Like Picasso said, "When there's anything to steal, I steal," so get stealing.

Works for Picasso.

1 - Fowler

You may have asked yourself who is the final arbiter of writing. It’s Fowler. Fowler’s Modern English Usage is the ultimate guide to writing in English.

Most writers will have a dictionary and a thesaurus. Or both. Modern English Usage, usually abbreviated just to 'Fowler' is the third essential book, although it is for some reason far more obscure and less often used.

First written by Henry Watson Fowler in 1926, it’s a guide for style and correct usage in English. More than a guide, the book is itself a good read. Fowler’s ascerbic observations and comments are funny, scathing and dryly, economically written. He walks the walk and talks the talk. Or maybe rights the write?

There are many ‘rules’ that writers should stick to, such as not splitting infinitives, not ending words with prepositions and such. Fowler says ‘piffle’ and ridicules the correct usage of grammar. He favours a ‘vigorous’ style. And he's persuasive.

The second edition, updated in 1965 by Sir Ernest Gowers, did away with many archaic and irrelevant entries. As English evolves, so does Fowler. The third edition is more controversial, almost completely rewritten by Robert Burchfield and abandoned many of Fowler's catty comments, replacing them with lighter explorations of English usage.

Stick to the first two editions if you can find them - the second edition is widely available.

Read Geoffrey Wheatcroft's celebration of Fowler here.

Fowler on split infinitives:

"The English-speaking world may be divided into (1) those who neither know nor care what a split infinitive is; (2) those who do not know, but care very much; (3) those who know & condemn; (4) those who know & approve; & (5) those who know & distinguish. . . . Those who neither know nor care are the vast majority, & are a happy folk, to be envied by most of the minority classes.

PS - Someone called Garner has produced a parallel tome for American English. If that interests you.

2 - Brian Eno - Oblique strategy cards

Developed by producer Brian Eno (you can hear his recent John Peel lecture here) and artist Peter Schmidt in the 1970s when Eno worked with David Bowie on the highly regarded Berlin trilogy of albums.

The deck is a pretty set of cards. Rather than pictures, each card has a message printed onto it. They are designed to help creative people get over those times when they are blocked, frustrated, bored, or when something is just not right. There is a web version here if you want to try them out.

Eno used the cards to take those Bowie albums to places they would not otherwise have gone. Many others swear by them as an indespensible way to get something new out of something mundane. Eno reputedly still uses them. Poet Simon Armitage is a fan, and made a documentary about them for the BBC you can listen to here.

The cards are sometimes scarily insightful, sometimes baffling, and often simply oblique. That’s the point - interpret them as you like and see where they take you.

Random Oblique Strategy card:

"Don't be afraid of things because they're easy to do"

3 - William Goldman - What lie did I tell next? (or more adventures in the screen trade)

A guide to writing, but writing screenplays.

William Goldman, pictured above with Sir Richard Attenborough during the fiilming of A Bridge Too Far, is one of the most successful screenwriters in history. He wrote Marathon Man. He wrote The Princess Bride. He wrote Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. He wrote the screen version of Misery. He’s also a novelist. He knows his shit.

This book is a sort-of sequel, sort of update to his earlier book, Adventures in the Screen Trade. That book concentrated on anecdotes and started looking at some screenwriting tips. This book delves much deeper. But it’s the go-to book for writers because it includes tips on setting scenes, dialogue and much more. Yes it’s pitched at screenwriters, but copywriters can learn a great deal from it.

Two example screenwriting tips copywriters can use:

- When writing a scene, arrive late. You don’t bother faffing around with introductions and smalltalk. Get to it.

- Compression. Convey a lot with not much. It's why people in films park directly outside the courthouse and never have to hunt for a parking space. Compression.

There are many more examples in the book, as well as some absolutely killer anecdotes on the madness of the screen industry, and why Clint Eastwood is not just a brilliant actor and director who brings his projects in under-budget, but why he’s personally admired too.

William Goldman reflects on his life and work above.

His thoughts on Hollywood:

"Nobody knows anything...... Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what's going to work. Every time out it's a guess and, if you're lucky, an educated one."

4 - Journalism - The Sewing Circles of Herat by Christina Lamb

Journalists have a lot to teach. They have to build their insight, sources and research to tell a good story. Much like copywriters do. If they fail to tell a good story, then nobody will read what they have written, and what's the use of that?

Journalists also use compression to help tell stories, using phrases that convey a lot quickly and simply. You can often see this in tabloid headlines. Tabloid writing, while supremely easy to read, is carefully crafted to convey the maximum possible in the shortest, simplest possible way.

Christina Lamb is not a tabloid writer, but a correspondent of the old school, totally immersed in her work and the stories that come out of it. She travelled through Pakistan and Afghanistan after interviewing Benazir Bhutto as a cub reporter on the Financial Times in the 1980s. She made the region her speciality and has written about the area many times throughout her career. What she doesn't know about the region is probably not worth knowing.

Lamb maintained a lifelong friendship with Bhutto and was there in the election convoy when Bhutto was assassinated in 2007.

This book delves into life in Afghanistan under the Taliban, and how the people defied the horrors going on around them as Afghanistan slipped back into the Dark Ages. It's a compelling read, difficult to put down. It puts into context much of the madness that continues in Afghanistan today.

For something a little more contemporary, try Detroit by Charlie LeDuff. It won the Pulitzer Prize, charting the decay of Motown and like much of the best journalism, reads like fiction.

5 - Childrens books - Maurice Sendak

Ask any author of chidrens literature. They will tell you that writing for children is hard. You not only have to be clear and concise, but you also have to be careful with your references because, as children, the readers might not be familiar with your references.

Most difficult are said to be picture books, which is why there are so many bad ones. But the good ones are kevlar-coated, bullet-proof brilliant things.

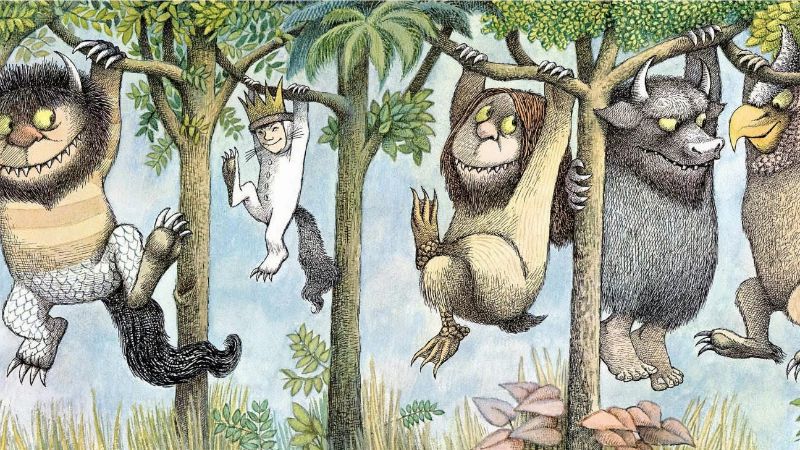

Take the Wild Things trilogy by Maurice Sendak. This is a series of three picture books about dreams and dreaming. Each story has a sense of unease and the surreal.

You have probably read some or all of these. They even inspire academic inquiry.

First is the original Where the Wild Things Are, where Max is sent to his room and escapes into his imagination to the land of the Wild Things. It was made into a film a few years ago.

Second is In the Night Kitchen. It's less well known, but as good as the original. Here, Mikey drifts into the night kitchen where he's baked into bread by bakers who resemble Oliver Hardy against a New York backdrop made from kitchen appliances and food packets. It’s sublime stuff. It’s also banned in some US states for its nudity. Which show's there’s no accounting for stupidity, I suppose.

Finally, and weirdest of the lot, is Outside Over There where Ida’s little sister is kidnapped by goblins and replaced with an ice baby. Ida must rescue her sister by falling out of the window blowing a hornpipe on her horn. This was Sendak's favourite, and he didn't produce anything else for 12 years. This was also apparently the inspiration for the 1986 David Bowie/Muppet film Labrinth.

None of the stories make any particular sense. Saying that, each book's world exists by its own rules that work perfectly. None of the books have more than about 200 words in total, but each tells its own surreal and complete tale. More compression.

What makes these stories so good is that they are designed to be read aloud, and the words practically jump from the page. The pictures are amazing too of course. When your kids constantly ask for the stories, which are now decades old, you know something is right.

Read Jonathan Jones' tribute to the trilogy here.

Sendak on Outside Over There:

"It was the story of me and my sister, basically. She’s Ida and her vexation, if not rage, in having to take care of me. To insinuate that as part of a relationship in a book for children is hard for critics because there’s a misconception of what is a children’s book and what it should contain and should not contain and what the subject matter should be and should not be. And primarily it is to be healthy and funny and clever and up-beat and not show the little tattered edges of what life was like. But I remembered what life was like and I didn’t know what else to write about."

Please login to comment.

Comments