Why we need brands

17 Apr 2015

Direct marketing is an act of persuasion and a brand simplifies the buying process by allowing the purchaser to dispense with the need to evaluate all of the elements of a product or service. Much direct marketing succeeds or fails at the point where the decision is made to engage (or not) with the material on offer.

The brand helps us to cross that threshold of uncertainty and deliver a piece of direct marketing by offering the reassurance of the values that we associate with a brand.

As such, direct marketers are guardians of their clients’ brands.

Where did brands come from? Wally Olins says in his book Corporate Identity (1989) that the first identities were the simple battle flags hoisted to tell the soldier on the ground where his side were in the heat of the fight. But there’s more to a brand than just an identity. At its heart, a brand is the promise of an experience.

Most people crave order and lives in which rules are clearly understood. Brands reinforce that sense of order. That may sounds like a hard statement to justify - but it’s a characteristic that runs very deeply.

‘It seems that, as adults, we may not believe in Father Christmas but we do believe in The Jolly Green Giant.’

As far as I know, there has never been a civilisation that didn’t invent or adopt a religion to help it make sense of where it belonged in the order of things. The ancient Greeks knew about geometry, the solar system, map making and natural sciences and they came up with the concepts of philosophy and democracy. However they also believed in a squad of Olympian gods and goddesses with clearly defined job descriptions. Some ancient Greek philosophies preferred the idea of a single deity and while in the words of Christopher Hitchens they may have been “moving nearer to the true round number,” they still felt happier and more secure with a mystical captain at the celestial helm, despite all their learning and intellectual capacity.

There is a cognitive dissonance between being able to understand that the earth revolves around the sun on the one hand and believing that a family of supernatural powers lives on Mount Olympus, on the other. We’re no better. In the same way, we might guess that in essence all makes of porridge are much the same, while paying more for a box of oats because it has a picture of a man in a kilt on it.

Brands help us by confirming our view of the world and our position in it. Needing to belong to something is a deep-seated need. and the more we feel threatened, the greater the desire to associate ourselves with something bigger. In his book Chasing the Scream (2014), Johann Hari looks at the causes of addiction and substance abuse. His conclusion is that just like lab rats, human beings respond to external social stresses by becoming addicted.

There is rarely a chemical dependency - just a social dependency to continue doing what they have done. He cites how when police in Vancouver managed to virtually stop the street supply of heroin, the illegal drug industry responded by selling packages that contained virtually no trace of the drug - but neglected to inform their customers. None of the addicts noticed the difference, apart from a few who grumbled about the quality of supply. No one went cold turkey and the addicts went about their usual lives, stealing to raise money to pay for a placebo. What they were addicted to, in effect, was their lifestyle. Buy the same token, brands are an embodiment of lifestyle, which is why we place so much value on them.

Hari says that history shows that it is at times of great societal stress that people become addicted. The UK’s agrarian revolution drove thousands of labourers away from the country and into the poverty of the urban world, where Gin Lanes, left, proliferated.

US troops in Vietnam became heavy cannabis users but turned to heroin when the army started using sniffer dogs to detect cannabis. At one point, the US had more heroin addicts in the armed forces in Vietnam than it did back home. But when the troops returned home, the only ones who remained addicted were those who had experienced traumatic childhoods (a common factor among addicts) or were addicts when they were conscripted.

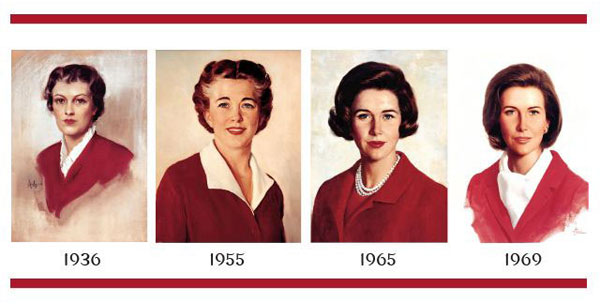

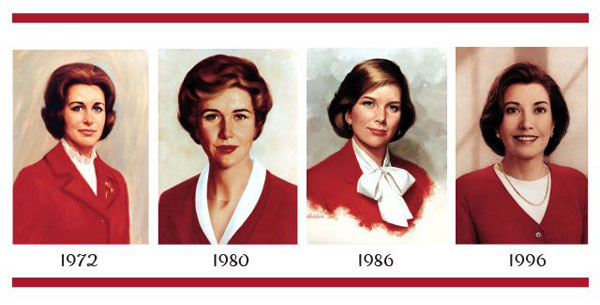

The changing face of eminent US cakeologist Betty Crocker

Modern brands arose from a time of rapid change and stress, as industrialisation and mass manufacture changed the way society operated. That’s why many of the oldest brands used personas to represent their products, such as Uncle Ben’s Rice (1943), Betty Crocker (1921) and The Quaker Oats Man (1877).

‘We are hard-wired to respond to faces as a matter of evolutionary survival.’

From 1890, Pears Soap used Bubbles, a painting of a young boy by Millais, to embody its brand values. On the other hand, cut-price brands like Tesco’s Everyday Value with its blue and white stripes or Asda’s Smart Price, with its utilitarian green and beige, are not offensive to the eye but are deliberately dressed down to be devoid of personality.

Dr. Siu Lan Tan, in an article in Psychology Today in 2013, argued that we are drawn to faces as a matter of survival. “We must register quickly if there is a stranger in our midst, and sense if this is a friendly or threatening presence. In short, we may be hard-wired to focus on faces as they provide information that is fundamentally important to our physical and social survival.”

Dr. Siu Lan Tan, in an article in Psychology Today in 2013, argued that we are drawn to faces as a matter of survival. “We must register quickly if there is a stranger in our midst, and sense if this is a friendly or threatening presence. In short, we may be hard-wired to focus on faces as they provide information that is fundamentally important to our physical and social survival.”

We grow to possess an unreasonable amount of faith in such brands. Research at Oregon State University shows that brand loyalists are (quite surprisingly) more adversely affected and disappointed if they feel that they have been let down by a brand that has a human face. It seems that, as adults, we may not believe in Father Christmas but we do believe in The Jolly Green Giant.

We love our brands. The recent BBC TV series, Eat Well for Less, focussed on the potential savings that can be made to a household budget, by switching to cheaper brands. Over the course of a week, a family eats only white-labelled produce and is challenged at the end of the experiment to say whether they prefer their normal brands or the cheaper substitutes. Just to balance things up a little, some premium brands are not swapped out but simply white labelled. In most cases the guinea pig family are unable to differentiate between premium brands and cheaper substitutes.

Older readers may recall Danny Baker (with hair) and the days of the Daz doorstep challenge TV campaign and reflect that over the last 20 years, the idea for a 40-second advert has been stretched out to fill three hours of primetime TV. The family on the BBC show has not been cured of its addiction to brands – it has simply been shown the logic of changing brands to save money. But things are shifting in the retail world, and brands are at the heart of it all. The growth of the big German discount supermarkets is undoubtedly due to their low prices. Most UK shoppers don’t have a clue about the brands that Lidl and Aldi sell because they have never heard of them.

Older readers may recall Danny Baker (with hair) and the days of the Daz doorstep challenge TV campaign and reflect that over the last 20 years, the idea for a 40-second advert has been stretched out to fill three hours of primetime TV. The family on the BBC show has not been cured of its addiction to brands – it has simply been shown the logic of changing brands to save money. But things are shifting in the retail world, and brands are at the heart of it all. The growth of the big German discount supermarkets is undoubtedly due to their low prices. Most UK shoppers don’t have a clue about the brands that Lidl and Aldi sell because they have never heard of them.

The shoppers have dropped their traditional brand loyalties to a product - and switched it to the supplier instead. Which is why it is so difficult for the UK’s established supermarkets like Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons to combat the German competitors by reducing prices on individual items. There is one competitor who has, in effect, stepped out of the fray. Waitrose, having wrapped itself in a middle-class cloak of warm mumsy sustainability, competes on the strength of its own brand values and not on the prices of its products. Even this hasn’t saved Waitrose entirely from the cold blast of commercialism. Last week’s news showed that Aldi has just bumped Waitrose down to seventh place in the battle for market share.

‘Let the brand speak for itself…’

So if we are hard-wired to focus on faces and familiarity as a means to survival what can we do as direct marketers to protect our client brands? We have a tiny window of opportunity in which to make a mark. If most job interviews are effectively all over within a minute or two, we have about five seconds at most. The most important tool we possess in this situation is the existing power of our clients’ brands, and their ability to simplify the act of choice.

Clarity, plain language and consistency are paramount

So whether we are designing a direct marketing product, or managing its delivery, our responsibility is to let the brand speak for itself. Clarity of message is of the utmost importance, as is consistency of message across all channels. Plain language, concision and a desire to place nothing in the way of the communication process are the keys to success.

We can best demonstrate our creativity by doing nothing more than letting the consumer and brand look each other deeply in the eye and let their natural and deep-rooted love affair take its natural course.

Please login to comment.

Comments